Honoring Black History in Healthcare: The Lasting Impact of Henrietta Lacks

NOAH is proud to share and honor Black History Month with articles of just a few of the important, impactful, and life-saving stories of Black history and healthcare in America. One of our primary goals at NOAH is ensure quality healthcare for every member of our community. To do that, we will look at where we have been, what we have accomplished, and how we will collectively achieve this goal.

The Lasting Impact of Henrietta Lacks

In 1951, Henrietta Lacks, a young mother of five, was diagnosed with cervical cancer. Doctors at Johns Hopkins collected some of her cancer cells during her biopsy to diagnose the cancer. Some of these cells were sent to Dr. George Gey’s research lab, as was common with many other patients at this time.

The sample cells from other patients Dr. Gey collected and studied quickly died. Henrietta Lacks’ cells, however, were different. Instead of dying, Henrietta’s cells doubled every 20-24 hours. These remarkable cells, named “HeLa” cells after her first and last name, became the first immortal human cell line.

To this day, researchers continue to use HeLa cells to make scientific and medical discoveries. They have allowed scientists to study the human genome, test the effects of drugs and toxins on human cells, learn more about cancer cells and viruses, and even create the Polio vaccine; all without having to experiment on humans. HeLa cells also have been used to improve our understanding of diseases like tuberculosis and HIV.

Despite her enormous contribution to medicine, however, the way in which Henrietta’s cells were used raised ethical questions. In the 1950s, it was common for extra biopsy samples to be shared and used for research without gaining consent from patients. Standardized informed consent was not common practice.

When Henrietta Lacks consented to the diagnosis and treatment of her cervical cancer, she was not informed that her cells could be collected and used for ongoing research. Additionally, there were no regulations on the use of human cells for research and patients did not have access to their medical records. The ethical concerns surrounding the use of Henrietta Lacks’ cell line have guided policies that now protect patients. These include informed consent, research approval through an Institutional Review Board (IRB) and improving patients’ access to their medical records.

Henrietta Lacks died at the age of 31, within a short time of her cancer diagnosis. Although her life ended early, Henrietta Lacks’ legacy lives on through her HeLa cells, the impact of her story, and on research and medical ethics.

More on her story can be found in Rebecca Skloots’ book: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.

Read our other Black History Month snapshots:

Understanding the Tuskegee Study

The Lasting Impact of Henrietta Lacks

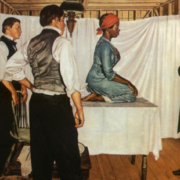

Enslaved Women and Modern Gynecology

Honoring Black History Month: Dr. Charles Richard Drew

Honoring Black History Month: Dr. Daniel Hale Williams

Honoring Black History Month: Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett

Honoring Black History Month: Dr. Alexa Irene Canady

Honoring Black History Month: Dr. James Durham